Table of Contents

When I first tried to create a budget, I overcomplicated it. I had 15 categories, color-coded spreadsheets, and a system so detailed that I abandoned it within two weeks. Sound familiar? The problem wasn’t discipline — it was complexity. That’s when I discovered the 50 30 20 budget rule, and it completely changed how I manage my money.

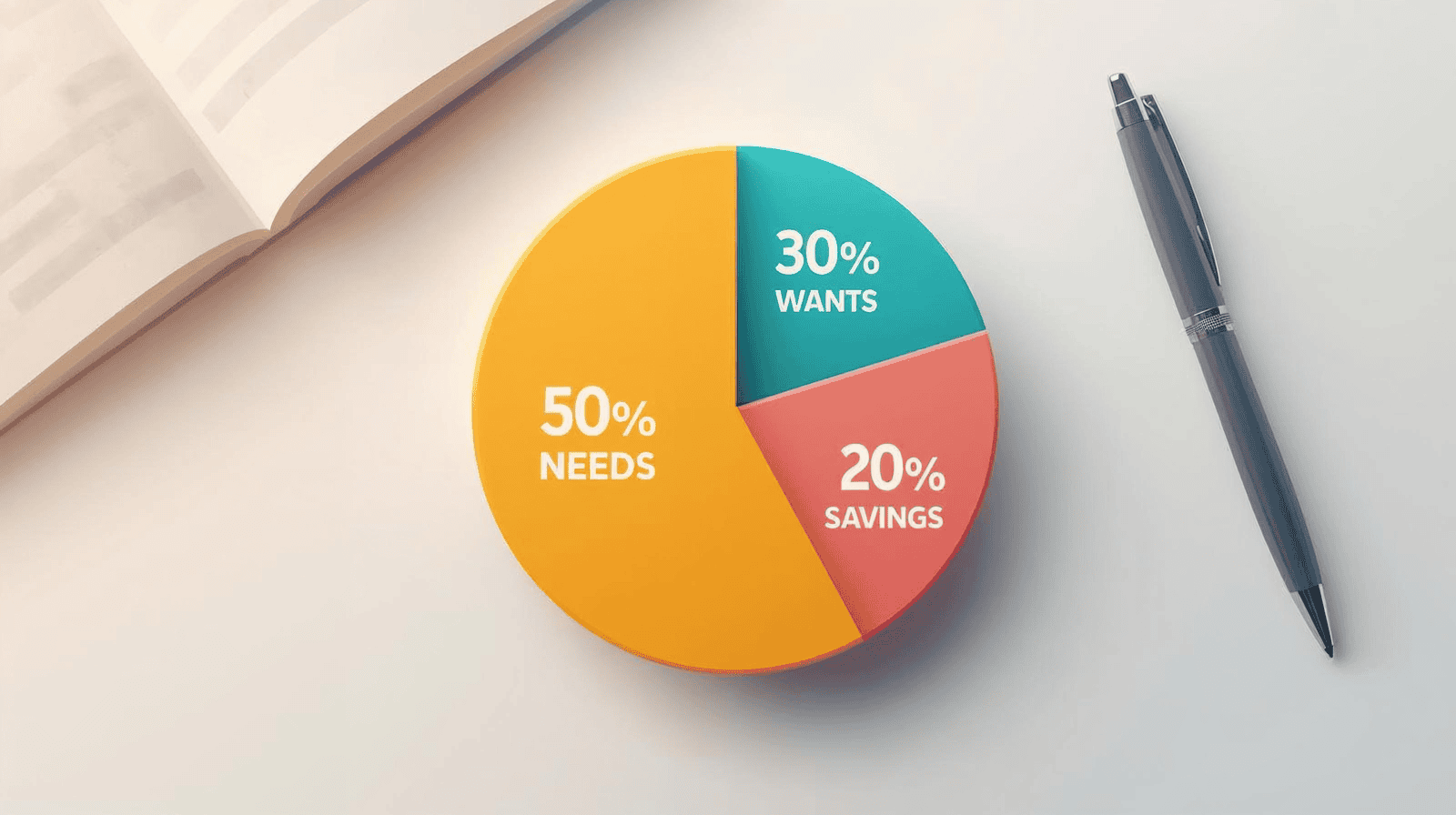

The 50/30/20 budget rule is one of the simplest and most effective budgeting frameworks ever created. It splits your after-tax income into three clear categories: 50% for needs, 30% for wants, and 20% for savings and debt repayment. No spreadsheets with 30 columns. No tracking every single coffee. Just three numbers that give you complete control over your finances.

If you’ve struggled with budgeting before — or never tried because it seemed overwhelming — the 50 30 20 budget rule is the easiest starting point. Here’s exactly how it works, how to apply it to your income, and how to adjust it when life doesn’t fit neatly into percentages.

What Is the 50/30/20 Budget Rule?

The 50/30/20 budget rule was popularized by Senator Elizabeth Warren and her daughter Amelia Warren Tyagi in their book All Your Worth: The Ultimate Lifetime Money Plan. The framework divides your after-tax (take-home) income into three buckets:

- 50% — Needs: Essential expenses you must pay to live and work

- 30% — Wants: Non-essential spending that improves your quality of life

- 20% — Savings & Debt: Money directed toward your financial future

The beauty of this system is its simplicity. You don’t need to track every dollar across dozens of categories. You just need to ensure your spending roughly aligns with these three percentages. According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, starting with a simple framework like this significantly increases the likelihood of sticking with a budget long-term.

The 50%: Needs — What Counts as Essential

Your needs are expenses you genuinely cannot avoid. These are the bills and costs that keep you housed, fed, healthy, and able to work. Half of your after-tax income should cover these.

Needs typically include:

- Housing — Rent or mortgage payment (including property tax and insurance)

- Utilities — Electricity, water, gas, internet (basic plan)

- Groceries — Food for home cooking (not dining out)

- Transportation — Car payment, gas, insurance, public transit

- Health insurance — Premiums, essential medications

- Minimum debt payments — Minimum payments on loans and credit cards

- Childcare — If required for you to work

The key distinction: needs are things that would cause serious consequences if you stopped paying. If you’d lose your home, your job, or your health, it’s a need. If life would just be less fun, it’s a want.

What if your needs exceed 50%? This is common, especially in high cost-of-living areas. If your needs consume 60% or more of your income, that’s a signal to look for ways to reduce fixed costs — downsizing, refinancing, or finding ways to save money on utilities and groceries. Our guide on frugal living on one income covers strategies for bringing essential expenses under control when money is tight.

The 30%: Wants — Spending That Makes Life Worth Living

Wants are everything you spend money on that isn’t strictly necessary for survival. This is the category most people either blow through or feel guilty about. The 50 30 20 budget rule gives you explicit permission to spend 30% of your income on things you enjoy — guilt-free — as long as your needs and savings are covered first.

Wants typically include:

- Dining out and takeout — Restaurants, coffee shops, food delivery

- Entertainment — Streaming subscriptions, concerts, movies, hobbies

- Shopping — Clothing beyond basics, electronics, home décor

- Travel and vacations — Trips, hotels, experiences

- Gym membership — Unless medically required

- Upgraded services — Premium phone plan, faster internet, nicer car than you need

The 30% allocation is not a minimum — it’s a ceiling. If you can spend less on wants and redirect the difference toward savings, you’ll build wealth faster. But the framework acknowledges that a budget you can’t enjoy is a budget you won’t follow.

If your wants spending is hard to track, our guide to the best free budgeting apps in 2026 can help you see exactly where your money goes each month.

The 20%: Savings and Debt Repayment — Building Your Future

The final 20% of your income is the wealth-building engine of the 50/30/20 budget rule. This money goes toward securing your financial future — both by saving and by eliminating debt.

This category includes:

- Emergency fund contributions — Until you have 3-6 months of expenses saved

- Retirement savings — 401(k), IRA, or other retirement accounts

- Extra debt payments — Anything above the minimum payment (minimums are counted under needs)

- Investments — Index funds, stocks, or other investment vehicles

- Sinking funds — Saving for specific future expenses (car repair, holiday gifts, annual subscriptions)

The priority order matters. I recommend building your emergency fund first — having 3-6 months of expenses saved protects you from going into debt when life throws a curveball. After that, focus on high-interest debt, then retirement savings.

If 20% feels impossible right now, start with whatever you can — even 5% is better than nothing. The habit of directing money toward savings matters more than the exact percentage. You can increase it as your income grows or your expenses shrink.

How to Apply the 50/30/20 Budget Rule to Your Income

Let’s make this concrete with real numbers. Here’s how the 50/30/20 budget rule looks at different income levels:

If your monthly take-home pay is $3,000:

- Needs (50%): $1,500

- Wants (30%): $900

- Savings/Debt (20%): $600

If your monthly take-home pay is $4,500:

- Needs (50%): $2,250

- Wants (30%): $1,350

- Savings/Debt (20%): $900

If your monthly take-home pay is $6,000:

- Needs (50%): $3,000

- Wants (30%): $1,800

- Savings/Debt (20%): $1,200

To calculate yours: take your monthly paycheck after taxes and deductions, multiply by 0.50, 0.30, and 0.20. Those are your three spending targets.

Understanding your net worth is an important part of assessing your financial health, which is why we’ve created a comprehensive article explaining how to calculate it.

How the 50/30/20 Rule Compares to Other Budgeting Methods

The 50/30/20 budget rule isn’t the only framework out there. Here’s how it stacks up against other popular approaches:

50/30/20 vs. Envelope Method: The envelope budgeting method uses physical cash in labeled envelopes for each spending category. It’s more granular and hands-on, which works well for people who overspend with cards. The 50 30 20 rule is broader and simpler — you can use it with any payment method.

50/30/20 vs. Zero-Based Budget: A zero-based budget assigns every dollar a specific purpose until you reach zero. It’s more precise but also more time-consuming. The 50/30/20 rule gives you flexibility within each category without tracking every individual transaction.

50/30/20 vs. 80/20 Rule: The 80/20 rule is even simpler — save 20% and spend 80% however you want. The 50/30/20 rule adds useful structure by distinguishing between needs and wants within that 80%.

None of these methods is universally “best.” The best budget is the one you’ll actually follow. For most beginners, the 50 30 20 budget rule hits the sweet spot between simplicity and structure.

When to Adjust the 50/30/20 Percentages

The 50/30/20 split is a starting framework, not a rigid rule. Life circumstances often require adjustments:

High cost-of-living area: If rent alone takes 40% of your income, you might need a 60/20/20 split temporarily. The goal is to work toward reducing that needs percentage over time.

Aggressive debt payoff: If you’re carrying high-interest credit card debt, a 50/20/30 split (flipping wants and savings) can help you eliminate debt faster. Understanding the difference between good debt and bad debt helps you decide how aggressively to prioritize repayment.

High-income earner: If you earn well above your needs, you might adopt a 40/20/40 split — reducing needs spending and supercharging savings and investments.

Irregular income: Freelancers and gig workers can still use this framework by basing percentages on their average monthly income. Our upcoming guide on budgeting with irregular income covers this in detail.

The percentages are guidelines. What matters is the habit of consciously dividing your income into these three categories rather than spending first and saving whatever’s left.

5 Tips to Make the 50/30/20 Budget Rule Work

1. Automate your savings first. Set up automatic transfers to your savings account on payday. If the 20% leaves your checking account before you see it, you won’t be tempted to spend it.

2. Use a budgeting app to track categories. Apps like YNAB, Mint, or PocketGuard can automatically categorize your spending into needs, wants, and savings so you know where you stand in real time. See our picks for the best free budgeting apps to find one that fits your style.

3. Review monthly and adjust. Spend 15 minutes at the end of each month reviewing your actual spending against the 50 30 20 targets. Small adjustments each month prevent big problems from building up.

4. Be honest about needs vs. wants. That premium gym membership? Want. That daily $6 latte? Want. It’s easy to rationalize wants as needs, but honesty here is what makes the system work.

5. Start with what you can. If 20% savings isn’t possible right now, start with 10% or even 5%. The framework still works — you’re just building toward the full 50/30/20 split as your financial situation improves.

Start Using the 50/30/20 Budget Rule Today

The 50/30/20 budget rule works because it’s simple enough to remember, flexible enough to adapt, and structured enough to actually change your financial trajectory. You don’t need a finance degree or a complex spreadsheet — you just need to know three numbers.

If you’ve been living without a budget, this is the easiest on-ramp into financial control. If you’ve tried budgeting before and given up, this framework might be the one that finally sticks.

For a complete overview of budgeting strategies and how to build a system that works for your life, read our comprehensive guide on how to budget and save money for beginners.

FAQ Section

Is the 50/30/20 rule based on gross or net income?

The 50/30/20 budget rule is based on your net (after-tax) income — your take-home pay after federal and state taxes, Social Security, and Medicare have been deducted. If you have pre-tax retirement contributions through your employer, you can count those toward the 20% savings category.

What if my needs are more than 50% of my income?

This is common, especially in expensive cities. Start by identifying which needs can be reduced — negotiate bills, find cheaper insurance, reduce transportation costs, or consider a roommate. Use the 50% target as a goal to work toward, even if your current reality is 55-65%. Any movement toward that target improves your financial position.

Where do minimum debt payments go in the 50/30/20 rule?

Minimum required payments on loans and credit cards fall under the 50% needs category because they’re obligations you must meet. Any extra payments above the minimum go into the 20% savings and debt repayment category, since those are voluntary choices that improve your financial future.

Is the 50/30/20 rule good for paying off debt?

It’s a solid starting point. The 20% savings portion can be directed heavily toward debt repayment, especially high-interest debt like credit cards. If you’re carrying significant debt, you can temporarily adjust to a 50/20/30 split — reducing wants to 20% and putting 30% toward debt and savings until balances are cleared.

Can couples use the 50/30/20 budget rule together?

Yes. Combine your total household take-home income and apply the percentages to the combined number. This works whether you have joint accounts, separate accounts, or a hybrid approach. The key is agreeing on what counts as needs vs. wants for your household.

How is the 50/30/20 rule different from the envelope method?

The 50/30/20 rule divides income into three broad categories by percentage, giving you flexibility within each bucket. The envelope method assigns specific dollar amounts to many individual categories (groceries, gas, entertainment) and uses physical cash to enforce limits. You can actually combine both — use the 50/30/20 framework for overall structure and envelopes for categories where you tend to overspend.

Toyin Onagoruwa is the founding editor of BrokeMeNot. With over five years of experience in personal finance writing and a background in financial services, he helps everyday people navigate credit cards, budgeting, and smart money management. Connect with him on LinkedIn.